Courtesy of data collected by the JWST, scientists recently announced that they may have detected chemicals associated with life in the atmosphere of an exoplanet with the euphonious name K2-18 b. K2-18 b is believed to be a “Hycean world,” an ocean world with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere. Think of it as a cross between Neptune and Earth (minus those pesky continents).

To be honest, SF authors prefer their life-bearing worlds to be more Earthlike than K2-18 b. About the only author who comes to mind as having used anything like K2-18 b is Hal Clement in his novel Noise (discussed here). However, coming at they do from a planet whose surface is three quarters ocean-covered, SF authors often made use of even soggier worlds. Take these five classic examples.

The Man Who Counts by Poul Anderson (1958)

Sincere regards are sent to master trader Nicholas van Rijn in the form of a bomb on his starship. The bomb fails its primary purpose of killing van Rijn outright, but it succeeds in marooning van Rijn and his companions on the surface of vast, metal-poor Diomedes. This may be the functional equivalent of murdering the master trader and company.

The good news is, there is a human trading base on Diomedes. All the other news is bad: van Rijn and company are on the wrong side of a vast ocean, they have no radio, the local biochemistry is poisonous to them, and while there are native Diomedeans to whom the humans could appeal for help, the Diomedeans on hand are engaged in a bitter war and in no mood to help seemingly useless aliens. Luckily, van Rijn has boundless reserves of cunning and a comprehensive lack of ethics.

One of the aspects I enjoy about Anderson’s work is that he understood that planets are larger than a Paramount Studio backlot. Thus, while the traders have learned a Diomedean language, it isn’t a primary language where they are—basically, the castaways are in the position of trying to get one or both of the two sides in the Hundred Years War to help them circumnavigate Earth, having previously mastered Japanese.

The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula Le Guin (1971)

Magic-rich Earthsea has no continents, only an abundance of islands. This vast archipelago is dominated by the Hardic cultures save in the north, where the pale Kargish peoples hold sway. The two cultures disagree on fundamentals, with Kargish seeing their neighbors as a nest of evil wizards, while the Hardics see the Kargish as uncouth barbarians.

Marked by fate, Tenar was raised from childhood to be a faithful priestess of the Kargish Nameless Ones. The Nameless Ones may not be gods but they are powerful and they demand service. Aspects of her duty upset Tenar, but childhood indoctrination leaves her no choice but to persevere in her designated role… until meddling sorcerer Ged intrudes into Tenar’s life on a quest of his own, and upends Tenar’s world.

In theory, Tenar is in a position of authority. In practice, Kargish culture is extremely patriarchal. A lot of effort is invested to ensure Tenar never gets it into her mind to step outside of her designated narrow role or even to be able to conceive that disobedience is an option. I am sure the author had no real-world parallels in mind.

Tatja Grimm’s World by Vernor Vinge (1987)

Exploration killed wonderous tales of lost civilizations on the Continent. Too challenging to support rich, complex societies, the largely barren Continent is home only to barbarians and impoverished primitives. Only the abundant riches of this world’s islands can provide the surplus needed for civilization.

Continent-born Tatja Grimm holds the dull-witted masses in contempt. Convinced that a greater fate awaits her, she sets out to find it in the civilized world. Disappointment greets her—Tatja’s peers are almost unknown on her native world. If she wants to find equals, she will have to find a path to the stars.

It’s not quite true that exploration killed Lost Civilization stories. It undermined their plausibility. To the distress of the editor who is one of the protagonists, the pulp writers of this backwater world refuse to drop a popular trope just because it is flat-out impossible.

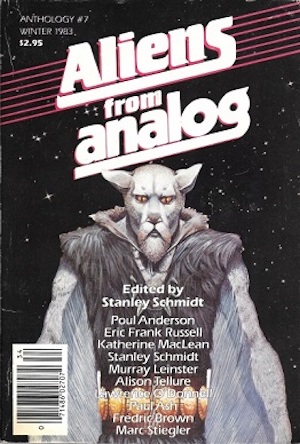

The FirstOne Stories by Alison Tellure (1977 to 1984)

Tellure’s four short stories document the life of FirstOne, the dominant lifeform of a distant world orbiting a blue-white star. This vast protean entity is by necessity ocean-dwelling. Its tools are limited to the products of its own body. Nevertheless, FirstOne is as close to a god as this planet will see.

FirstOne is curious, relentless, and ruthless. It does not hesitate to create spawn to explore regions out of its reach. When the spawn becomes a potential threat, FirstOne does its best to exterminate them. FirstOne’s undoing will be its ignorance: it has no idea what allies its spawn found living on the continents.

It’s disappointing that Tellure did not have a longer career and that with just four stories in the sequence—”Lord of All It Surveys” (1977)

“Skysinger” (1977), “Green-Eyed Lady, Laughing Lady” (1982), and “Low Midnight” (1984)—there are not enough FirstOne stories to justify a collection (although I suppose if novellas can carve out a niche, so can exceedingly brief short story collections). The author is still alive, as far as I know, so perhaps one day we will see more stories from her.

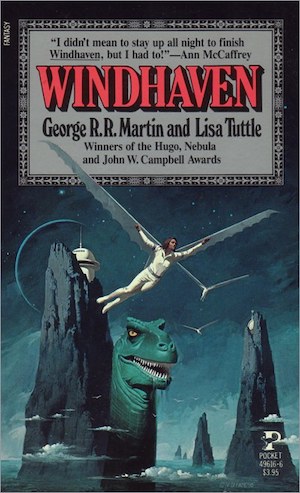

Windhaven by George R. R. Martin and Lisa Tuttle (1981)

Windhaven is a world of storms, small islands, and monster-filled seas, a place only castaways with no choice would settle. Windhaven is also a world of low gravity and dense atmosphere. The flyers maintain communication between islands, using wings constructed from starship metal. Thus, Windhaven has one civilization rather than an assortment of isolated, fragile island nations.

Maris is determined to be a flyer. Jealous of the dwindling supply of wings, flyers embrace strict inheritance. The only way to become a flyer is to inherit the wings from a parent. Or, as the people of Windhaven discover to their immense surprise, by being an extremely determined young woman set on introducing her culture to the concept of meritocracy.

I am sure it will surprise and alarm readers to discover that people who have heretofore been assured of lofty social status simply by being born into the correct family are hostile to the idea of opening their profession to people who are actually good at it. Where do SF authors get their ideas?

***

Of course, ocean worlds abound in SF. This is just a small sample and I may have missed some of your favorites. If so, feel free to mention them in comments below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.